By 2020, 80 percent of humans will live in cities. As mobile and digital communications evolve, are there better ways for cities to engage citizens than conventional paper-based public notices and mailings?

Probably. This past fall I engaged Code for America (CfA) in an MPA Experiential Learning project to explore this question. CfA is a nonprofit that brings technologists and local governments together to make cities better for everyone. (You may be familiar with CfA from a much-viewed TED talk by their founder Jennifer Pahlka.) Instead of taking on the entire paper-based notice system, CfA and I focused on a narrow question: How effective are conventional paper based notices and mailings at improving historic preservation decisions in Alamo Square?

Why historic preservation?

Why historic preservation?

Historic districts are often a focal point for neighborhood controversies about land use in cities. Effective citizen engagement can therefore be critical to good decisions.

Additionally, historic preservation often has important sustainability impacts. Improvement and reuse of existing infrastructure in historic districts not only sustains the aesthetic character and tangible cultural history of a place, but preserves embodied energy of existing materials, eliminates waste associated with demolition, and reduces the environmental impacts associated with new construction.

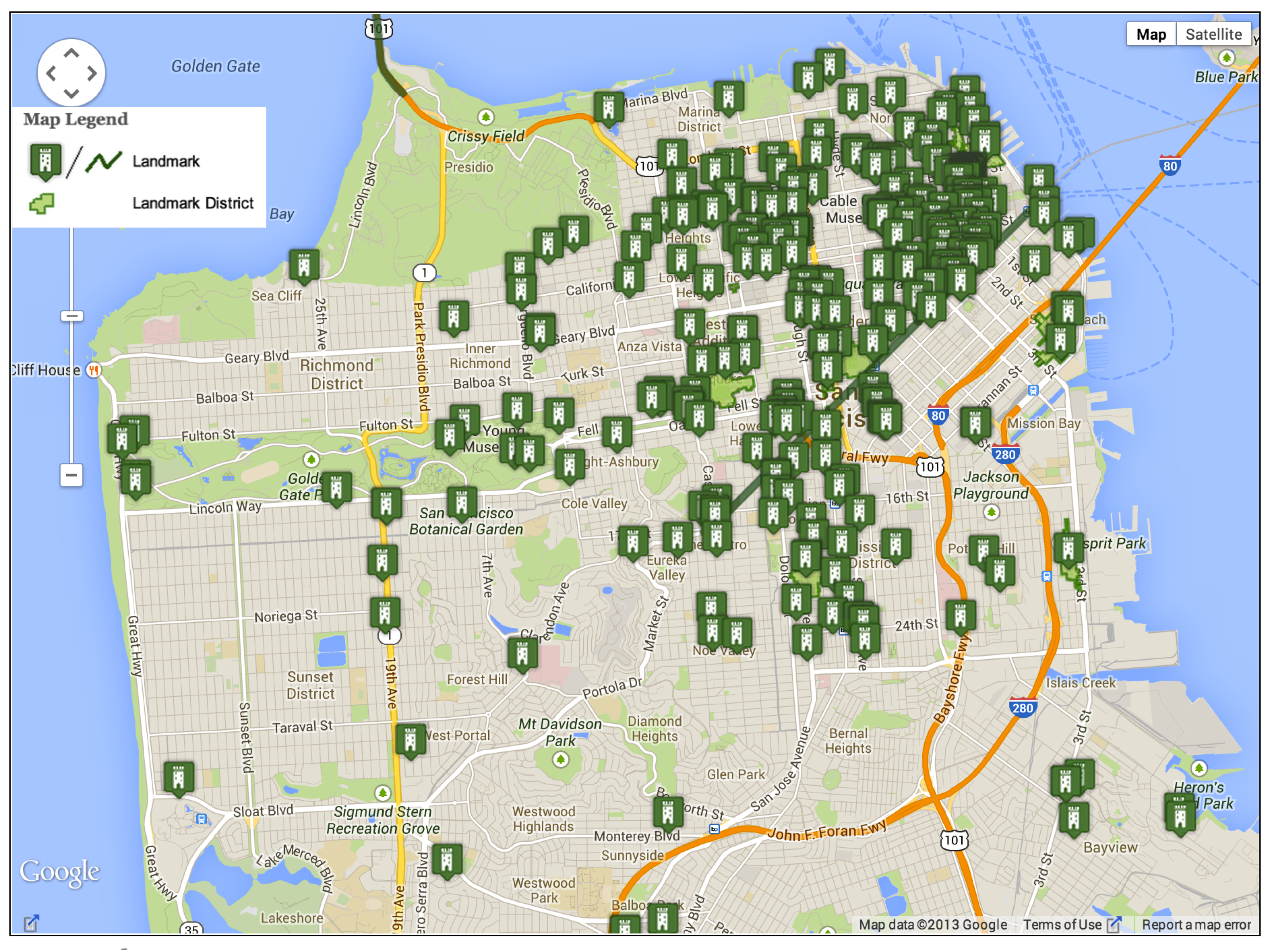

Historic preservation also provides an enormous economic and tourism boost to individual neighborhoods throughout San Francisco. For an idea of just how prevalent these districts are, take a look at the map of San Francisco Landmarks & Historic Districts (above).

Why Alamo Square?

Few historic districts mean as much to both locals and visitors as Alamo Square. From Full House to The Five Year Engagement, it’s frequently featured in popular media and symbolic of San Francisco’s row house aesthetic.

There also happened to be a live preservation issue in the district.

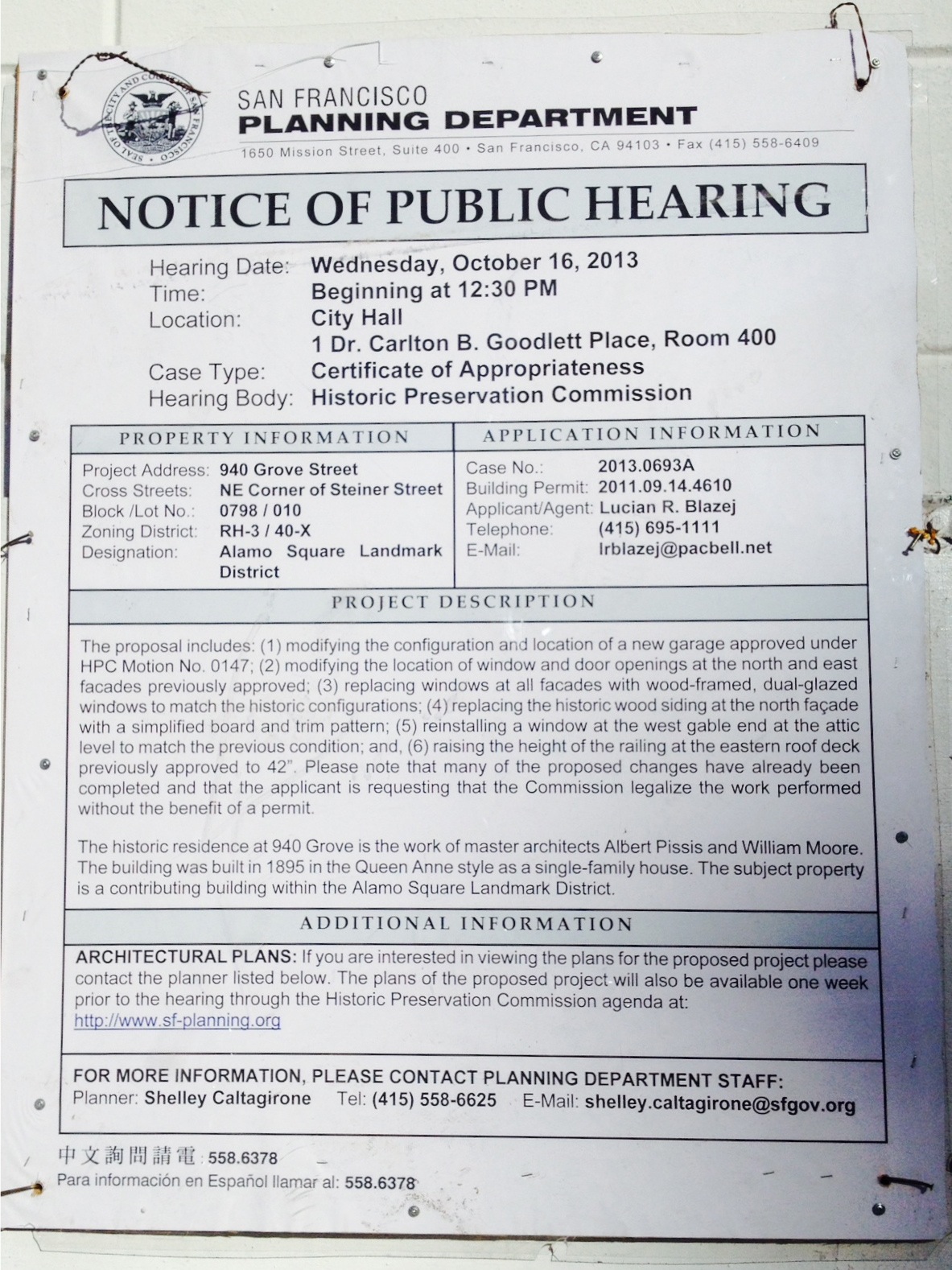

On the east side of the square, the renovation of an imposing house built in 1895 has been underway for over a year. The three-story residence at 940 Grove Street is the work of master architects Albert Pissis and William Moore and stands next to the Victorian “Painted Ladies” for which the square is famous. The structure, originally a single-family house, was used as a school between 1956 and 2010, but the Historic Preservation Commission (HPC) reviewed and approved a rehabilitation proposal to return the property to residential use by a previous owner.

In 2010, the property was sold to a new owner, who requested to modify the previously approved design and continued to make some modifications without prior approval from the planning department. The owner requested a Certificate of Appropriateness to legalize parts of the project that have already been completed and to approve further proposed alterations. A public notice (see photo) was posted in front of the property to invite citizens to the public hearing.

With the assistance of my Research Methods and Policy Evaluation professor Dr. Sara Schwartz, I traced the impact of this posted public notice as an example of the primary way cities alert local residents to historic preservation issues.

This included an online survey of about 400 residents living in the immediate vicinity of the property being renovated, in-person interviews of pedestrians and passers-by in the Alamo Square area, archival record review, and field observation, both on site and at HPC hearings.

What did I find?

What did I find?

Observing HPC hearings was instructive. At these meetings, the number of people who speak varies between zero to three per case, or between five to 50 for an entire hearing. When there are at least three people speaking about a single case, or five people during an entire meeting, citizen engagement is considered “high.” Assuming that each case being discussed during the meeting has the same level of importance, the current overall success rate of the public notice as a tool for civic engagement is 0.725%. Not very promising.

However, there are other ways residents find out about potential issues, such as online communications from the neighborhood association. This is the channel through which I conducted my survey.

The online survey had a response rate of 17% and revealed an engagement level higher than what would have been detectable from the HPC meetings alone. Of those who responded, 89% had seen the public notice, 78% had read it, and only 12% had ignored it. 22% expressed a willingness to engage while only 11% showed up at the hearing suggesting the time and/or day of the hearing is not convenient.

Those who didn’t attend the HPC hearing said that the time of the hearing was not convenient (65%), the date was not convenient (38%), the issue was not important (13%), or s/he simply didn’t care about HPC in general (13%).

In addition to detecting a higher potential engagement rate on specific cases, my online survey was also able to assess more general information about the attitudes of residents toward historic preservation. For example, I asked whether respondents’ opinion of the importance of the issue would change if the building was converted into a bar or a needle exchange center. If a bar, 89% said the issue would be more important, 56% would consider attending the public hearing, and 11% wanted to find out more details. If a needle exchange center, 100% said it would be more important, 55.56% would consider attending the public hearing, and one respondent wanted to find out more details. My intercept interviews also revealed that people, particularly property owners, are concerned about damage to the community fabric from any new development.

In a city like San Francisco, where technology rules, it does seem like the traditional paper-based, case-by-case Notice-and-Hearing process for civic engagement is ripe for a technology upgrade. Easier citizen engagement and better information certainly seem within reach. In the end, I was happy to provide some baseline data to CfA for use in advocating for both policy and citizen action to bring about those outcomes.

This article was originally published in Presidian Spring 2014: Theory to Action. Read more from the interactive online magazine here!